HANOI, Vietnam (AP) — An excessive climate phenomenon referred to as the dzud has killed greater than 7.1 million animals in Mongolia this 12 months, greater than a tenth of the nation’s complete livestock holdings, endangering herders’ livelihoods and lifestyle.

Dzuds are a mix of perennial droughts and extreme, snowy winters and they’re turning into harsher and extra frequent due to climate change. They’re most related to Mongolia but in addition happen in different elements of Central Asia.

Many deaths, particularly amongst malnourished feminine animals and their younger, happen in the course of the spring, which is the birthing season.

Herding is central to Mongolia’s financial system and tradition — contributing to 80% of its agricultural manufacturing and 11% of GDP.

In Mongolian, the phrase dzud means catastrophe. Dzuds happen when extraordinarily heavy snows trigger impenetrable layers of snow and ice to cowl Mongolia’s huge grasslands, so the animals can not graze they usually starve to dying. Drought at different instances of the 12 months means there’s not sufficient forage for the animals to fatten up for the winter.

Dzuds used to happen as soon as in a decade or so however have gotten harsher and extra frequent due to local weather change. This 12 months’s dzud is the sixth up to now decade and the worst but. It adopted a dzud final 12 months and a dry summer time. Snowfall was the heaviest since 1975.

The toll on Mongolia’s herds has soared, with 2.1 million head of cattle, sheep and goats lifeless in February, rising to 7.1 million in Could, in line with state media.

1000’s of households have misplaced over 70% of their complete herds. And the entire dying toll could improve to 14.9 million animals, or practically 24% of Mongolia’s whole herd, mentioned Deputy Prime Minister S. Amarsaikhan, according to state media.

Nomadic herding is so important for resource-rich Mongolia’s 3.3 million those that its structure refers back to the nation’s 65 million camels, yaks, cattle, sheep, goats and horses as its “nationwide wealth.”

Livestock and their merchandise are Mongolia’s second-largest export after mining, in line with the Asian Development Bank.

“The lack of the livestock has dealt an irreversible blow to financial stability and intensified the folks’s already dire circumstances,” Olga Dzhumaeva, the pinnacle of the East Asia delegation at Worldwide Federation of Pink Cross and Pink Crescent or IFRC, mentioned in an interview with The Related Press.

Excessive prices for gasoline, meals and fodder made the scenario a lot worse for herders like Gantomor, a 38-year-old herder in mountainous Arkhangai province. Like many Mongolians, he goes by one title.

Warnings of a dzud prompted Gantomor to promote his complete flock of about 400 sheep. He solely stored his sturdier yaks and horses, hoping that that he’d be capable of take them to pastures that wouldn’t be as badly affected, mentioned his sister-in-law, Gantuya Batdelger, 33, a graduate faculty pupil.

Even after spending greater than $2,000 to move the remaining 200-odd animals 200 kilometers (124 miles) to a spot he thought could be safer, he didn’t escape the dzud. Seventy yaks died and 40 horses left the herd, leaving him with lower than 100. “By promoting the sheep, (the household) had wished to avoid wasting cash. However they spent all of it,” mentioned Batdelger.

Batdelger’s brother-in-law was higher off than others. A buddy had all however 15 of her 250 yaks die.

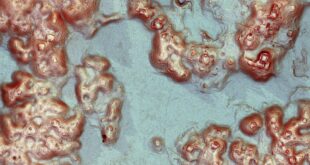

The Mongolian countryside was crammed with lots of of carcasses, piling up within the melting snow, she mentioned.

Disposing of the carcasses shortly to make sure they don’t unfold ailments is one other massive problem. By early Could, 5.6 million, or practically 80%, of the lifeless animals had been buried.

Hotter temperatures can deliver forest fires or mud storms. Heavy runoff from melting snow will increase the chance of flash floods, particularly in city areas. Many pregnant inventory, weakened from the winter, lose their offspring, typically as a result of they can’t adequately feed them, mentioned Matilda Dimovska, the UNDP’s resident consultant in Mongolia.

“It’s actually devastating to see, how (the infant animals) cry for meals,” she mentioned.

The dzud is an ideal instance of how interlinked local weather change is with poverty and the financial system, she mentioned. Herders who lose their herds usually migrate to cities just like the capital, Ulaanbaatar, however discover few alternatives for work.

“They enter into the cycle of poverty,” she mentioned.

The more and more routine nature of the dzuds has raised the necessity for Mongolia to develop higher early warning techniques for pure disasters, mentioned Mungunkhishig Batbaatar, the nation director of the nonprofit Folks in Want.

Combining know-how with community-level approaches works finest: “It’s estimated that nations with restricted early warning protection have catastrophe mortality that’s eight instances greater than nations with substantial to complete protection,” he mentioned.

In the meantime, worldwide help has been “very inadequate,” mentioned Dzhumaeva. An IFRC enchantment launched in mid-March has not reached even 20% of its goal of 5.5 million Swiss Francs ($6 million). Budgets strained by pressing responses to crises like Ukraine or Gaza are an element, she mentioned, “However this leaves little room for addressing the devastating results of dzud in Mongolia.”

Mongolia wants assist but it surely additionally must adapt to dzuds with methods akin to higher climate forecasting and measures to cease overgrazing. Herders have to diversify their incomes to assist cushion the influence of livestock losses.

Khandaa Byamba, 37, a camel herder who lives in Dundgobi province in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert mentioned in an internet interview that she has discovered from her elders and likewise the laborious expertise of repeated dzuds.

Seeing early indicators of one more dzud, she let her camels wander, counting on their very own instincts to seek out pastures. The household earlier determined to only herd camels to deal with local weather change, drought and deteriorating pastures which were turning into deserts. Khandaa Byamba’s husband adopted the animals for the primary 100 kilometers (62 miles) whereas she stayed behind with some youthful animals.

Because the snow piled up, different households reported dropping scores of animals. However after the winter, most of her camels returned. They solely misplaced three grownup camels and 10 youthful ones of their herd of greater than 200.

“This 12 months has been the toughest,” she mentioned.

______

The Related Press’ local weather and environmental protection receives monetary assist from a number of non-public foundations. AP is solely chargeable for all content material. Discover AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a listing of supporters and funded protection areas at AP.org.

Ferdja Ferdja.com delivers the latest news and relevant information across various domains including politics, economics, technology, culture, and more. Stay informed with our detailed articles and in-depth analyses.

Ferdja Ferdja.com delivers the latest news and relevant information across various domains including politics, economics, technology, culture, and more. Stay informed with our detailed articles and in-depth analyses.